Having written three posts in this space, and having run out of good ideas for more, I decided to dip into my email files and recycle some desultory exchanges about books and related topics. Yes – I know; it’s the lazy man’s solution, but HL Mencken did it all the time (except, of course, for the email bit) — introducing a piece in the Baltimore Sunpapers, recycling it in the American Mercury or Smart Set, reusing it again in the Prejudices books, and exhuming it one final time for the Chrestomathy. Most of his biographers express great admiration for his thrift and efficient use of available resources, and they should do no less for me.

Having written three posts in this space, and having run out of good ideas for more, I decided to dip into my email files and recycle some desultory exchanges about books and related topics. Yes – I know; it’s the lazy man’s solution, but HL Mencken did it all the time (except, of course, for the email bit) — introducing a piece in the Baltimore Sunpapers, recycling it in the American Mercury or Smart Set, reusing it again in the Prejudices books, and exhuming it one final time for the Chrestomathy. Most of his biographers express great admiration for his thrift and efficient use of available resources, and they should do no less for me.

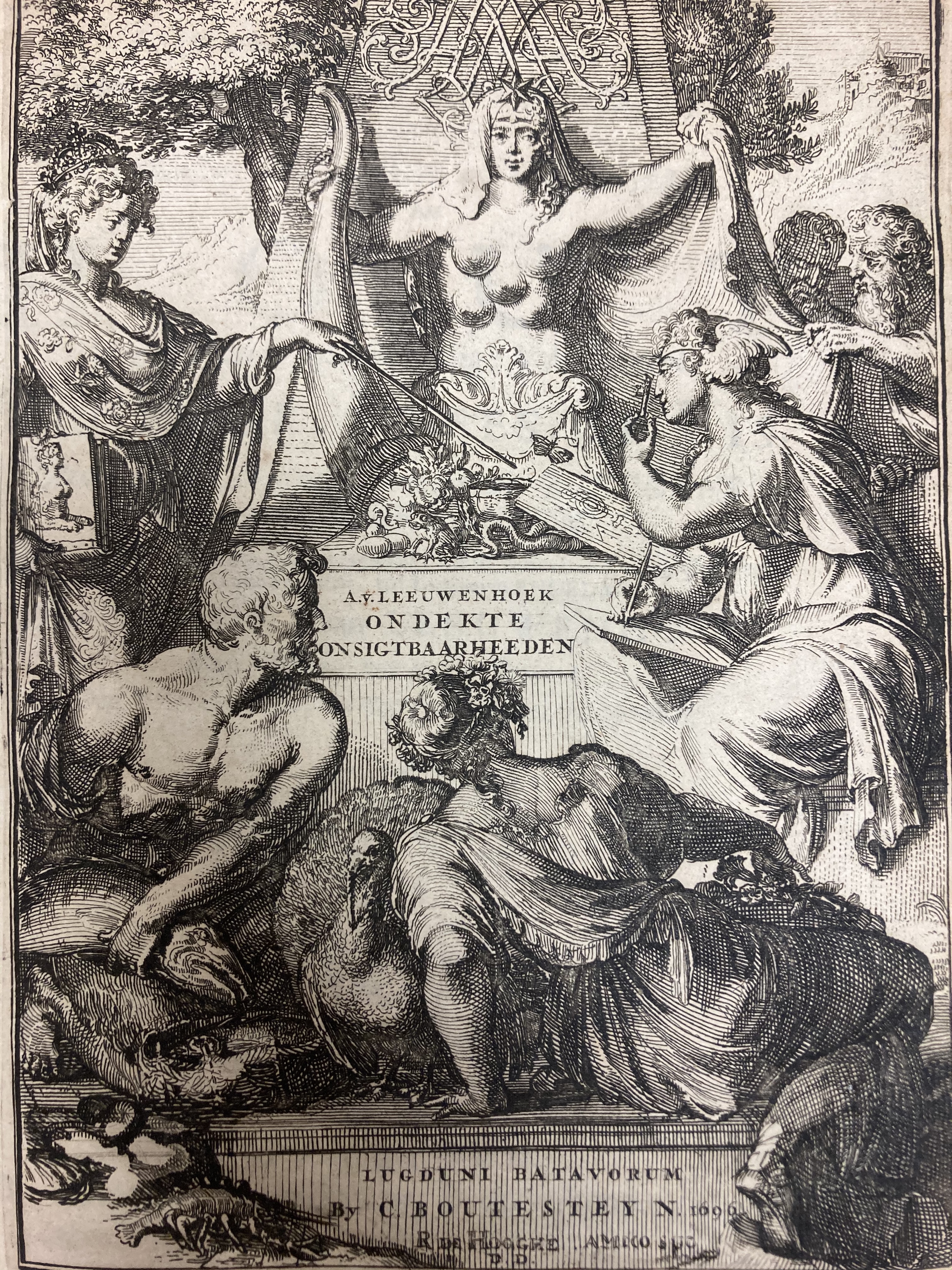

1. There’s something very odd about this image from the frontispiece to Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s Arcana Naturae, Ope & beneficio exquisitissimorum Microscopiorum…, a work known to its friends as Dobell 25b, after Leeuwenhoek’s bibliographer Clifford Dobell.

It is not clear who, or Who, is depicted here, although similar images have been described as representing a wide variety of goddesses or personages, including Artemis, Demeter, and Venus. Jubal Harshaw, of Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, was probably thinking of a similar image when he swore an oath “by the multiple paps of Venus Genetrix.”

Fortunately, an explanation is at hand. The University of Chicago Press has lately been issuing collections of essays on art by the late Leo Steinberg — collections that are thoughtfully edited (by Sheila Schwartz), and copiously illustrated. The most recent volume, just out, covers “Renaissance and Baroque Art.” In the first chapter of that book, Steinberg discusses the history of such images in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, quoting among others St. Jerome, who claimed that “[t]he Ephesians worshiped the many-breasted Diana … and apparently by this image they would falsely show her to be the nurse of all beasts and living things.” Steinberg demonstrates, fairly conclusively I think, that the “Unidentified Pendant Objects” in the earliest such images (ancient sculptures of the goddess Artemis) had no nipples and weren’t intended to be breasts at all — interpreting them as such was a later error that, like most errors, was able to run around the world while Truth was still getting its boots on. Since the nineteenth century, “several suggestions have been proffered about the UPOs; they are bull’s testicles, rows of a hunting bag of Hittite origin …; amber pendants attached to the original statute. But most scholars of the last half century agree that some decoration had been later mistaken as breasts — perhaps by Christians intent on making this heathen idol seem monstrous.”

2. I read The Seagull for the first time in my life this weekend, in Tom Stoppard’s translation; and also watched the excellent 2018 movie version with Annette Bening as Arkadina, Saoirse Ronan as Nina, Brian Dennehy as Sorin, Elisabeth Moss (the secretary-turned-copywriter from Mad Men) as Masha, and Mare Winningham (a member of the Brat Pack! From St. Elmo’s Fire! Playing an old woman!?) as Polina. I came across the following from Act IV, which seems particularly heartbreaking these days:

Medvedenko: May I ask you, Doctor, which foreign city did you like best?

Dorn: Genoa.

Konstantin: Why Genoa?

Dorn: The crowds in the streets. When you step out of your hotel in the evening, the streets are swarming with people. You drift along with the crowd this way and that, back and forth, it’s got a life of its own and you become part of it, body and soul, you start to think there really might be a universal spirit like the one Nina acted in your play. …

Relatedly (I guess) a recent issue of Notes and Queries has an interesting piece of literary detective work concerning a statement in one of Katherine Mansfield’s letters — “[I]t is not easy to be simple, it is not just (as A. T.’s friend used to say) a sheep sneezing.” “Not just a sheep sneezing” turns out to be a line from one of Chekhov’s letters, “A.T.’s friend” is the Russian journalist Vladimir Gilyarovski, and “A.T.” is Chekhov himself. Why “A.T.” instead of “A.C.”? For the same reason as Chebyshev polynomials are conventionally abbreviated as Tn(x) — because the Russian letter Ҷ used to be transliterated as “Tch”. How about that! (The line from Chekhov is “[T]o write a fairly good story and give the reader ten to twenty interesting minutes – that as Gilyarovsky says, is not a sheep sneezing …” That translation, by the way, is from Constance Garnett’s 1920 work, titled “Letters of [wait for it …] Anton Tchehov”.)

3. “The weather in Yalta is wonderful and fresh, my health has improved. I don’t even want to leave here to go to Moscow, I’m working so well, and it’s so pleasant not to feel any itch in my anus such as I’ve had all summer.” — Letter from Anton Chekhov to Maxim Gorky, October 16, 1900

Chekhov wrote the above while working on Three Sisters, which I’ve spent the last few days reading and reading about. Over the weekend I watched the 1970 movie version directed by Lawrence Olivier, with wonderful performances by Alan Bates (as Vershinin), Derek Jacobi (as Andrei), Olivier himself (as Chebutykin), and Joan Plowright (as Masha). The eponymous sisters, each in their 20s in Act 1, are living unhappily in an unnamed town in the provinces (a “town such as Perm,” Chekhov tells Gorky in the letter quoted above), having been dragged there eleven years earlier by their father, a military officer who was sent to command a base in the town. All the sisters can talk about, through all four acts, is how uncultured the town and its people are, and how they long to go back to Moscow — yet somehow they never manage to leave their unsatisfying jobs and/or marriages, buy a train ticket, and actually make the trip. (Maybe I’m being a little unfair here. Michael Frayn, who prepared the translation I am reading, checked contemporary Baedekers and concluded that the trip would take at least a few days, assuming that the town in which the sisters live is about as far from Moscow as Perm is. Still, four days on a train is not exactly six months in a covered wagon on the Oregon Trail.) This reminded me of “Waiting for Godot” (“VLADIMIR: Shall we go? ESTRAGON: Yes, let’s go. [They do not move.]”) I was so taken with the connection that I did some research, and learned — as, alas, with so many of my “discoveries” — that the connection between Chekhov and Beckett is old news. I’m still claiming credit, however, and writing off my predecessors as anticipatory plagiarists.

In any event, I doubt that the sisters would have been happy in Moscow (as more than one character in the play tells them) — I gather that the Muscovites of 1900 were all busy bitching about how nekulturny Russia was, and longing for Paris or London, where there was real civilization.

So I’ll take my leave now of Olga, Masha, and Irina Prozorova, their brother Andrei, and their author, who was last heard from in Yalta, with a bad case of idiopathic pruritis ani ….

4. From a review by John Updike of “Max in Verse,” a collection of Beerbohm’s poetry:

“On the copyright page of his first book, The Works of Max Beerbohm, Max found the imprint

London: John Lane, The Bodley Head

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons

“Beneath it, he wrote in pen:

This plain announcement, nicely read

Iambically runs.”

-Prospero