by Abigail Haber

Note: The summer after my first year at Brown, I had the wonderful privilege of working at Manhattan Rare Books. Learning through, photographing, thinking and writing about rare books stoked an interest in them, one that’s been important to my growth during college. As a recent graduate, I look back on my time at college–through the books I’ve read, documents I’ve seen, and words I’ve shared with loved ones.

–––––––––––

1. My hands slide back and forth along my hips–it’s a nervous tic I picked up in high school. October in Rhode Island feels similar to October back home: but, the sea chill in the air makes it feel a little different, more biting.

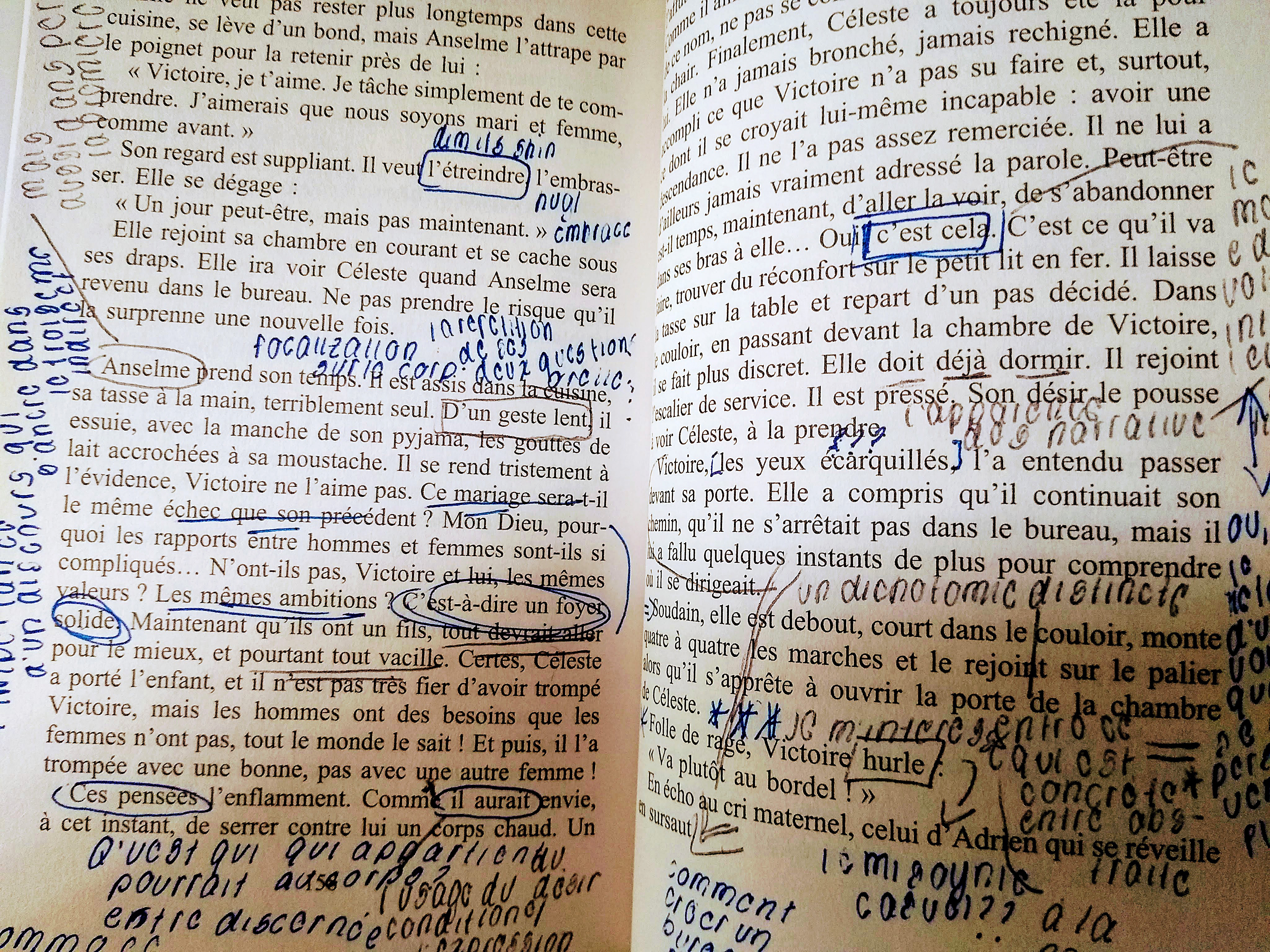

I take out a book from my backpack, flipping through it to prepare my thoughts before class. There is a kind of celebration to its unveiling, because it is the first one I bought at the university bookstore. It is also the first book I will read by myself, in French, at Brown: Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert. 17-year-old Abby had very little in common with the interior, adulterous, yearning Emma; I think present-day Abby has even less similarity. But, the experience of holding and reading that book–reading that book in the language in which it was originally penned–was (and is and will be) a humbling one.

I take out a book from my backpack, flipping through it to prepare my thoughts before class. There is a kind of celebration to its unveiling, because it is the first one I bought at the university bookstore. It is also the first book I will read by myself, in French, at Brown: Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert. 17-year-old Abby had very little in common with the interior, adulterous, yearning Emma; I think present-day Abby has even less similarity. But, the experience of holding and reading that book–reading that book in the language in which it was originally penned–was (and is and will be) a humbling one.

I will always hold close the first French book that humbled me, that set me onto a path of furious underlining, and readerly empathy and responsibility, and falling asleep into big books, and radical transformation.

Outside the classroom that day, I will lose the lucky red pencil I used religiously during high school. I wonder what Emma Bovary would have had to say about these kinds of new beginnings.

2. I sit in the back of the university’s archives. I’m in Paris, in a windowless room in the 5th arrondissement. The librarian sets down a cellophane-wrapped document on the desk in front of me. It’s an old copy of the Vichy laws, a series of statutes instituted during the Nazi occupation of France, ones that systematically called for the dehumanization, deportation, and extermination of French Jews. I knew I was going to see this document (I asked for it, after all) and, yet, the simple gesture of having it in my hands shocked me into a state of silence.

I clap my hand over my mouth and cry into my palm. It is not a big room, but I think I can see the dead, people that history has never identified well enough to name, piling up against the walls. Families like my very own; girls that looked and prayed like me; fathers that lost and wept and searched after all that could have been searched for was long gone. How much power and pain–silent, quiet, aching pain–an old piece of paper can contain!

3. I am sitting in a library with a person who will come to be one of my closest friends. Gingerly, we leaf through the beautiful, leather-bound text together, a 19th century medical treatise written by a famous Parisian doctor. He writes about the procedures he performed on his patients, the patients he chose to treat and not treat, and the history of the field.

A lot of detail. And yet, there is so much missing out. There are no details about the women whose babies he helped to deliver. He does not address the thousands of men and women left unattended because they were too poor, because they lived or loved or looked different.

No one tells us to whisper. But we do, because we are two heads bent penitently during a silent prayer of sorts. We read in awe: a text about people that could have been us, and written by a man who could never have been us.

Pushing open the large double doors, my sneaker crunches firmly down on a leaf that has gotten caught in the door jamb. It is yellow, a little veiny, seems relatively sturdy despite the wear it has suffered in all that swinging open and closing shut.

Sometimes we get the amazing chance to ponder about, touch, and be touched by words on paper that look a lot like trampled leaves. And sometimes, there are other texts (that look, in many ways just the same, albeit with different authors) that go unseen. Perhaps because they aren’t allowed to be seen, because they’ve been hidden away, or because they were never allowed to be written in the first place. Here’s to finding more manuscripts that let us, that incite in us a desire to probe this open space.

4. There are only a few objects left in my near-empty room, the most notable being a pile of books. Fitting. It is move-out day and almost graduation–well, it is almost the day of almost-graduation. It is hard to count a Zoom ceremony as a proper substitute.

I peel open Flaubert’s book that I had bought all those years ago. Faded but still visible are pencil marks made during my first year at Brown. In larger and more rounded writing is pen marks put to paper in a class I took only a semester ago. First-year Abby and Senior-Year Abby refute, remark on, make jokes about, draw arrows between each other. All versions, times, and people exist at once: all lifetimes are here.

Maurice Blanchot, a famous French thinker, wrote about the power of reading–or, more specifically, the idea that a person who reads a text can reify its existence, turn it into something new and unique and intimate. I think Blanchot knew what he was talking about; books breathe, change, take on new lives for the people that read and love them. If books have biography, perhaps my notes in-text are a kind of self-made afterlife–a vital, life-giving constellation that soars through and out of my body, stringing up a night so bright it’ll be impossible to dim.

Holding this all in my hands, I am lucky it gets to be my goodbye.