––––In honor of the second anniversary of Tom Wolfe’s death: May 14, 2018––––

Note: This is a blog post from a guest contributor – a long-time collector of many subjects. He would like to remain anonymous, but so you may recognize future posts by him, we’ll call him “Prospero”.

I was inspired to write this post after reading the recent memoirs of Jamie Bernstein, the daughter of the Leonard Bernstein. (Famous Father Girl: A Memo of Growing Up Bernstein; HarperCollins 2018.) Jamie is unsparing and insightful about her family, but she is somewhat less tolerant of criticism from outsiders. She was, in particular, royally cheesed off by Wolfe’s hilarious, classic deconstruction of the Egregio Maestro’s It-Was-A-Meeting-Damn-It-Not-A-Party for the Black Panthers. (“Radical Chic: That Party At Lenny’s”; New York Magazine, June 1970.) She describes Wolfe as a “rascally young journalist” who “managed to sneak in” to the Not-A-Party; and although she apparently was not present, goes on to picture him “silently ingesting all of it, like a python gradually swallowing a rabbit whole.” She ends on a generous note, conceding that Wolfe may not have understood “the degree to which his snide little piece of neo-journalism rendered him a veritable stooge for the FBI.”

* * *

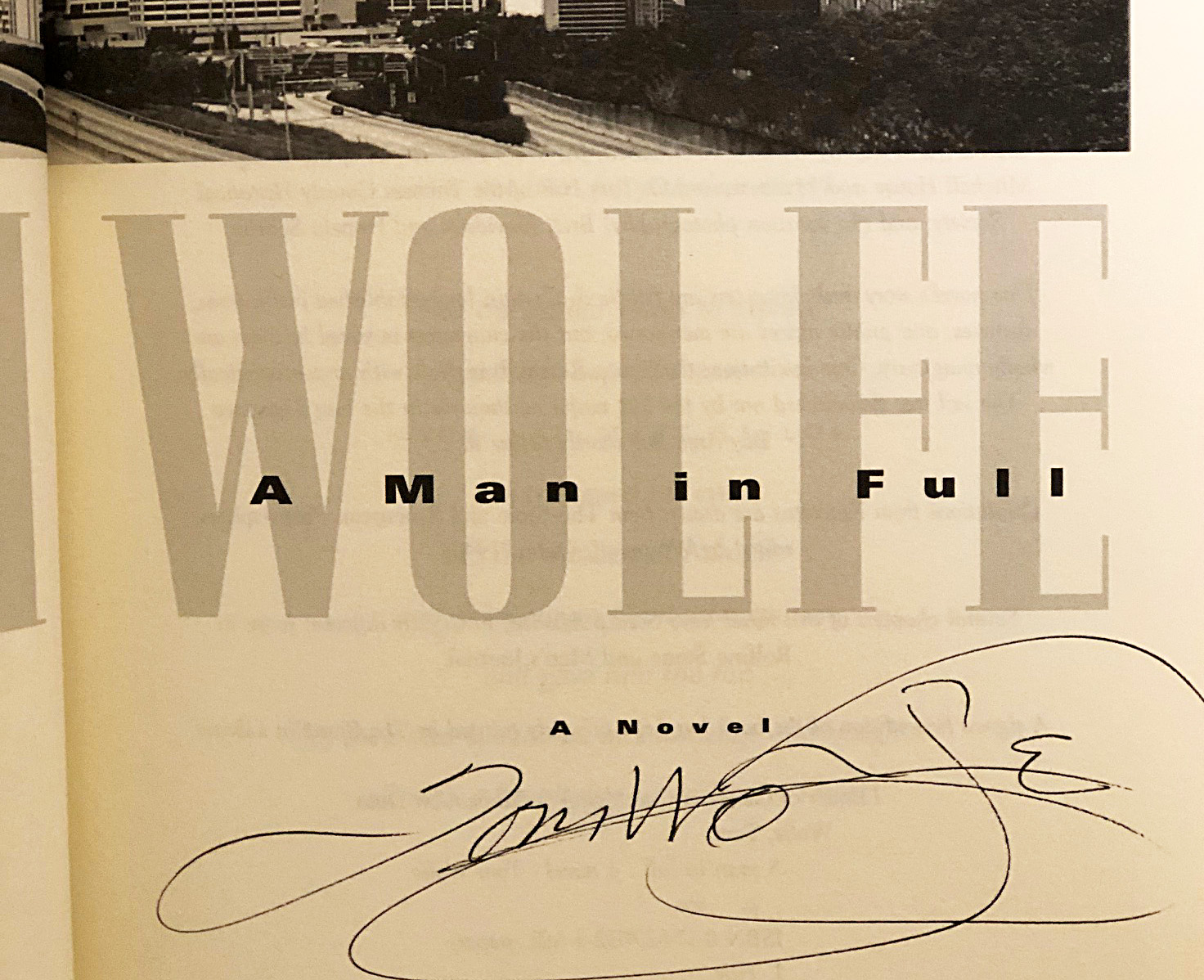

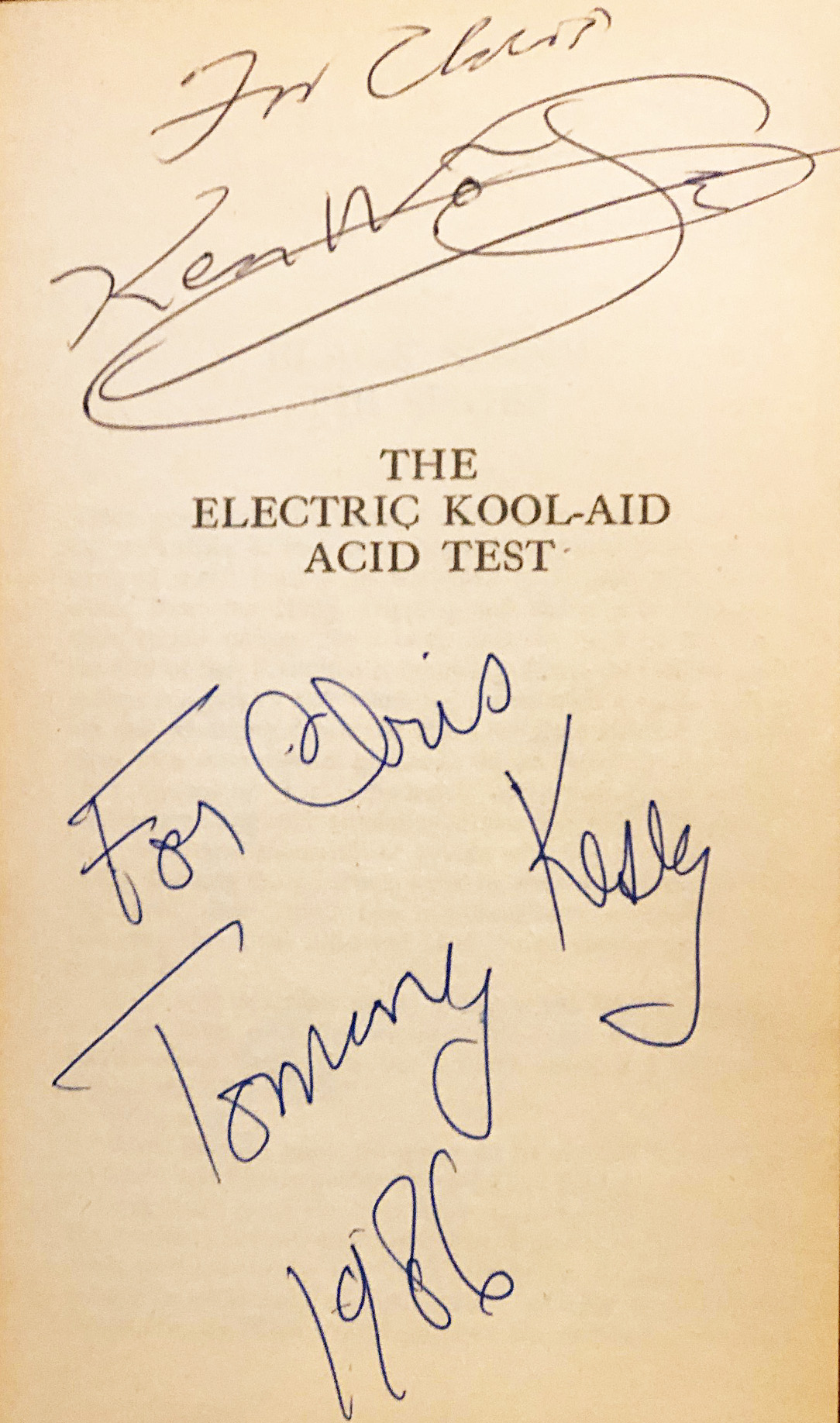

Despite being hosted by my friends at Manhattan Rare Books, this post will not be primarily about collecting, and if it belongs on this site at all it is because it deals with books. I will note, however, that Wolfe is a great subject for collectors — particularly of association copies — because of Wolfe’s florid (in style and calligraphy) inscriptions, sometimes illustrated by sketches. There are also some multiply inscribed copies out there. Finding a first edition of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test signed by Wolfe and Ken Kesey is a good start, and you can earn still more brownie points for each additional Merry Prankster signature. (Modesty prevents me from mentioning the fact that my copy of The Right Stuff is signed by Wolfe and John Glenn and Chuck Yeager.) But let me get back to the subject announced by my title.

Despite being hosted by my friends at Manhattan Rare Books, this post will not be primarily about collecting, and if it belongs on this site at all it is because it deals with books. I will note, however, that Wolfe is a great subject for collectors — particularly of association copies — because of Wolfe’s florid (in style and calligraphy) inscriptions, sometimes illustrated by sketches. There are also some multiply inscribed copies out there. Finding a first edition of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test signed by Wolfe and Ken Kesey is a good start, and you can earn still more brownie points for each additional Merry Prankster signature. (Modesty prevents me from mentioning the fact that my copy of The Right Stuff is signed by Wolfe and John Glenn and Chuck Yeager.) But let me get back to the subject announced by my title.

What I love most about Wolfe is his “eye.” Wolfe was simply the best observer around for noticing all of the nuances of how people spoke and thought and behaved. He had all the observational ability and insight of an anthropologist, but turned inward, towards his own mid-century American culture. (And of course the hardest thing to observe is one’s own culture, because everything about it is hidden in plain sight, too commonplace to be noticed.)

Let me give you an example. You are eating lunch in a restaurant; the kind of restaurant — such as an old-fashioned coffee shop or a diner — where you are expected to pay in cash at the door, on the way out, rather than handing your credit card to the waiter at your table, as you used to do at Elaine’s, or paying before you eat, as you do at McDonald’s. Let’s say your check is $8, so the standard procedure is to leave a buck and a quarter or a buck fifty on the table as a tip, and then go to the cashier to pay your eight dollars. But you don’t have a dollar bill or any quarters — just a ten. So what you have to do is leave your seat, walk to the cashier’s desk, pay your bill with the ten — being sure to ask for a dollar of your change in silver — and then walk back to the table, leave the tip, and go. But there’s a problem, and you know it. Once you’ve left the table the first time, you know — you just know — that everyone in the restaurant, particularly your waiter, is going to be staring at you with contempt, because you are obviously going to leave the restaurant without leaving a tip. What a cheapskate! You just can’t bear having everyone think that of you, even for a second.

So what do you do? Easy — you leave something at the table as a signifier of the fact that you will return. It may be your coat, or an umbrella, or a book, or your glasses, but you must leave something to indicate, as clearly as you can, that you will in fact return. Maybe some people will think that you just forgot your umbrella, and never really planned to return at all, but most will at least decide that they have to give you the benefit of the doubt, and will acknowledge that you may well be headed back to leave a tip. They may doubt you, but they won’t despise you.

How often have you participated in, or seen, this little scenario? Probably dozens of times if, like me, you grew up in the insecure American middle class of the 1960s or early 1970s. But did you think about what you were doing (or seeing), or think about why it was being done, or what it implied about you and your society? Of course not. “You see,” as Sherlock Holmes said to Dr. Watson, “but you do not observe.” (“A Scandal in Bohemia”; 1891) Well, Wolfe not only saw this elaborate self-protective gavotte, but he observed it, and then put a frame around it, as it were, identifying it as an interesting phenomenon worthy of thought and study. It was as if person after person had walked numbly in front of a screen with a few million colored pixels on it, until one day someone said, “What an interesting picture! Why, it’s an animal of some sort. I’ll call it a sheep.” Before Wolfe, it was something that just happened, unnoticed, from time to time; but Wolfe observed it, reified it, and even gave it a cute name. Then and forever after, the object left behind was known as a “tip hostage.”

A similarly insightful piece of noticing is Wolfe’s discovery of the “mid-Atlantic man,” the advertising executive whose employer was created by the merger of a British firm with an American one (like Don Draper’s firm, for at least a season or two), and who succeeds by following what Stephen Potter (“Lifemanship”; 1950) calls the “two-clubs stratagem,” acting like an American when in Britain and like a Brit when in America.

But the tip hostage and the mid-Atlantic man aren’t my favorite piece of Wolfean (Tom, not Nero) observation. That honor goes to “A Sunday Kind of Love,” an essay that you can most readily find in Wolfe’s first collection, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby. (They don’t make titles like that anymore.)

Probably the best thing to do at this point would be just to reproduce the entire essay here, so that you could read it in all its glory. But instead, I will just describe it for you, thereby forcing you to go out and buy a copy of Kandy-Kolored or “The Purple Decade,” you cheapskate (!).

“A Sunday Kind of Love” starts with some sharp description of the tension and hustle of young and upwardly mobile people living in Manhattan. And the stress-for-success doesn’t even end on Friday. “There is Saturday, but Saturday is not much better than Monday through Friday. Saturday is the day for errands in New York.” And “[t]rue, there is Saturday night, and Friday night. … But for the dalliance of love, they are just as stupefying and wound up as the rest of the week. On Friday and Saturday nights everyone is making some kind of scene.”

“And, then, an unbelievable dawning; Sunday, in New York.” Wolfe paints a wonderful vignette of a youngish couple, unmarried and spending the weekend together, waking up late Sunday morning in her one-room Chelsea apartment, “in a brownstone sunk down behind a lot of loft buildings and truck terminals and so forth.” They pass a long slow day enjoying the luxury of not having to be anywhere or do anything, feasting on scrambled eggs and smoked oysters and black bread and jam, reading the Sunday Times, listening to E. Power Biggs play the organ on the hi-fi. (Wolfe’s essay was written in 1965. There were things called hi-fi’s.) At one point “they take a long slow walk on the empty street,” relishing the absence of the “weasel millions bellying past you.” “All there was was the cocoon of love, which was complete.” “It was like taking peyote or something. This marvelously high feeling would come over them …, and the most commonplace objects took on this great radiance and significance.”

“Now that was love,” Wolfe’s informant (the male of the couple) tells him. And then, acknowledges sadly, “I don’t know what happens to it. Unless it’s Monday. Monday sort of happens to it in New York.”

Why is this my favorite, of all of Wolfe’s writing? Because as a piece of observation it is every bit as sharp as his identification of the institution of the tip hostage, delineating here the unique texture of Sundays in Manhattan, the luxury of torpor, and the wonderful feelings that come with a sudden, if temporary, release from great tension. But its subject — instead of being the lust, greed, envy, pride, gluttony, or insecurity that underlies our everyday life — is an epiphany, a sudden intrusion of joy and peace and light and grace into everyday life — a hint, to quote John Updike, “a mitigating hint, that the world is not entirely iron and stone and effort and fear.” (“A Month of Sundays” [no connection, despite the title, to Wolfe’s essay]; 1975)

And that’s what Tom Wolfe means to me.

–Prospero