Note: This is a blog post from a guest contributor – a long-time collector of many subjects. He would like to remain anonymous, but so you may recognize future posts by him, we’ll call him “Prospero”.

RESOLVING A SHAKESPEARIAN “CRUX”, OR, FIGHTING ON SLEDS

Shakespeare is full of wonderful puzzles, particularly those textual conundrums that modern editors refer to as “cruxes” (“[a] difficulty which it torments or troubles one greatly to interpret or explain, a thing that puzzles the ingenuity” — OED). I want to explain how one such crux led me to add to my collection of Shakespearian sources the first edition of a wonderful sixteenth-century treatise on Scandinavian customs by Olaus Magnus, the last Roman Catholic archbishop of Uppsala.

In Act I, scene 1 of Hamlet, Horatio, marveling at the ghost he had just seen, tells Marcellus that it was as much like old King Hamlet:

As thou art to thy selfe,

Such was the very Armour he had on,

When th’ Ambitious Norwey combatted:

So frown’d he once, when in an angry parle

He smot the sledded Pollax on the Ice.

‘Tis strange

I quote here from the First Folio of 1623, although the texts of the First Quarto of 1603 and the Second Quarto of 1604/5 are essentially identical for this passage (although each has “sleaded” in place of “sledded,” and spells “pollax” with a lower-case “p”) — thus freeing us, for once, of the necessity of figuring out which of the three versions we should credit.

The overall sense is fairly clear: King Hamlet was at war with “th’ Ambitious Norw[a]y” (kings in Hamlet are referred to by the names of their countries; King Claudius, for example, is frequently referred to as “Denmark,” or “the Dane”), and, while engaged in an angry discussion (“parle[y]”), he “smot[e]” something on the ice. (At this point I am sadly unable to resist the temptation to mention the parody of “Greensleeves” written by the 1960s Borscht-belt comedian Alan Sherman, in which the knight laments, “Oh, wouldst I could kick the habit, and give up smoting for good.”) But who or what did the King smite? What is, or are, “sledded Pollax”?

Editors have clustered around two interpretations of this passage. The great Shakespeare scholar Harold Jenkins, in his edition of Hamlet first published in 1982 for the Arden Shakespeare series, reads “Pollax” as “Pollacks” — i.e., Poles, in particular Polish soldiers. Jenkins, citing several instances, notes that “Polack,” with several variant spellings, is “normal Elizabethan for ‘Pole.’” (The word was not considered derogatory in Shakespeare’s day.) All right, but what are those Poles doing in the middle of a war between Denmark and Norway, and isn’t there something faintly farcical about a battle fought on sleds? And why is anyone fighting at all in the middle of a “parley” — which is generally understood to imply discussions intended to resolve, rather than prosecute, a dispute?

None of those difficulties bothered Jenkins, who discussed the subject at length in one of his “Longer Notes.” (Jenkins added a few dozen “Longer Notes” at the end of the play for those who weren’t sated by the not-exactly-short notes that occupy at least half of each page of the text.) He states that Poles “belong to the play’s background wars in which Norway is balanced by Poland and which are already being prepared for …. Shakespeare seems to have thought of these two countries as both bordering Denmark ….” He cites evidence that Scandinavians traveled on sleds in Shakespeare’s day. (So “Shakespeare would not be offending plausibility in imagining an encounter with sledded opponents on a frozen lake or sea.”) And he suggests that Horatio may have been using the word “parley” ironically, since “Shakespeare more than once uses the verb speak, in similar understatement, to mean ‘engage in combat.’”

The second interpretation is exemplified by Jonathan Bates’ General Introduction to the Royal Shakespeare Company’s edition of Shakespeare’s complete works (2007). (I quote here from the expanded version of the introduction that is available online.) Bates begins by noting the problems with the solution proposed by Jenkins and other editors: “Old Hamlet is combatting ‘Ambitious Norway,’ not Poland. A ‘parle’ is … a peace negotiation, not a battle. An iced-over river on the border between Denmark and Norway is an appropriate setting for the negotiation of a treaty, whereas the notion of a battle fought on ice is colourful but wildly implausible.” He adds that a search of databases of early-modern English texts — available now but not in Jenkins’ day — “reveals no other usage of the word ‘sledded’ or ‘sleaded’ in the period.”

Bates is led by these difficulties to read “pollax” as “pole-ax[e]” — “a weapon for use in close combat, existing in various forms but generally having a head consisting of an axe blade or hammer-head, balanced at the rear by a pointed fluke. … Now chiefly historical” (again, the OED). Well, why not? After all, in Act V, scene 4, King Claudius calls for his “Switzers” — mercenary Swiss troops; and even today members of the Vatican’s Pontifical Swiss Guard carry ceremonial pole-axes. And, Bates continues, “the absence of other occurrences of ‘sledded’ strongly suggests compositorial error; the occurrence of ‘steeled’ with pole-axe [in other texts] suggests the emendation ‘steeled pole-axe.’ During a parley with the Norwegians, angry Old Hamlet grabs the steel-headed pole-axe from the Switzer who stands guard beside him and bangs it emphatically on the ice.” Bates’ reconstruction sounded very plausible to me when I first read it. (And, incidentally, it lends some support to the depiction of King Hamlet in John Updike’s prequel “Gertrude and Claudius,” in which Claudius, through his act of regicide, rescues Gertrude from her angry, abusive husband.)

That is where matters more or less stood when Shakespeare scholar Julie Maxwell published an article in the summer 2004 issue of Renaissance Quarterly titled “Counter-Reformation Versions of Saxo: A New Source for ‘Hamlet’?” Maxwell’s article was primarily concerned with the sources of the Christian overlay that Shakespeare added to the pagan versions of the Hamlet (or Amleth) legend that Shakespeare had obtained, directly or indirectly, from Saxo Grammaticus’ Danorum Regum heroumque Historiae; and she found the key to that transition in the first and later editions of Olaus Magnus’ 1555 work, Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus. She notes that there were many points “at which [Shakespeare] could have drawn on the wealth of naturalist, ethnographic, popular, and antiquarian information that [Olaus’] Historia supplies.” More to the point here, however, in the course of teasing out the connections between Shakespeare and Olaus, she sheds a great deal of light on those “sledded Pollax.”

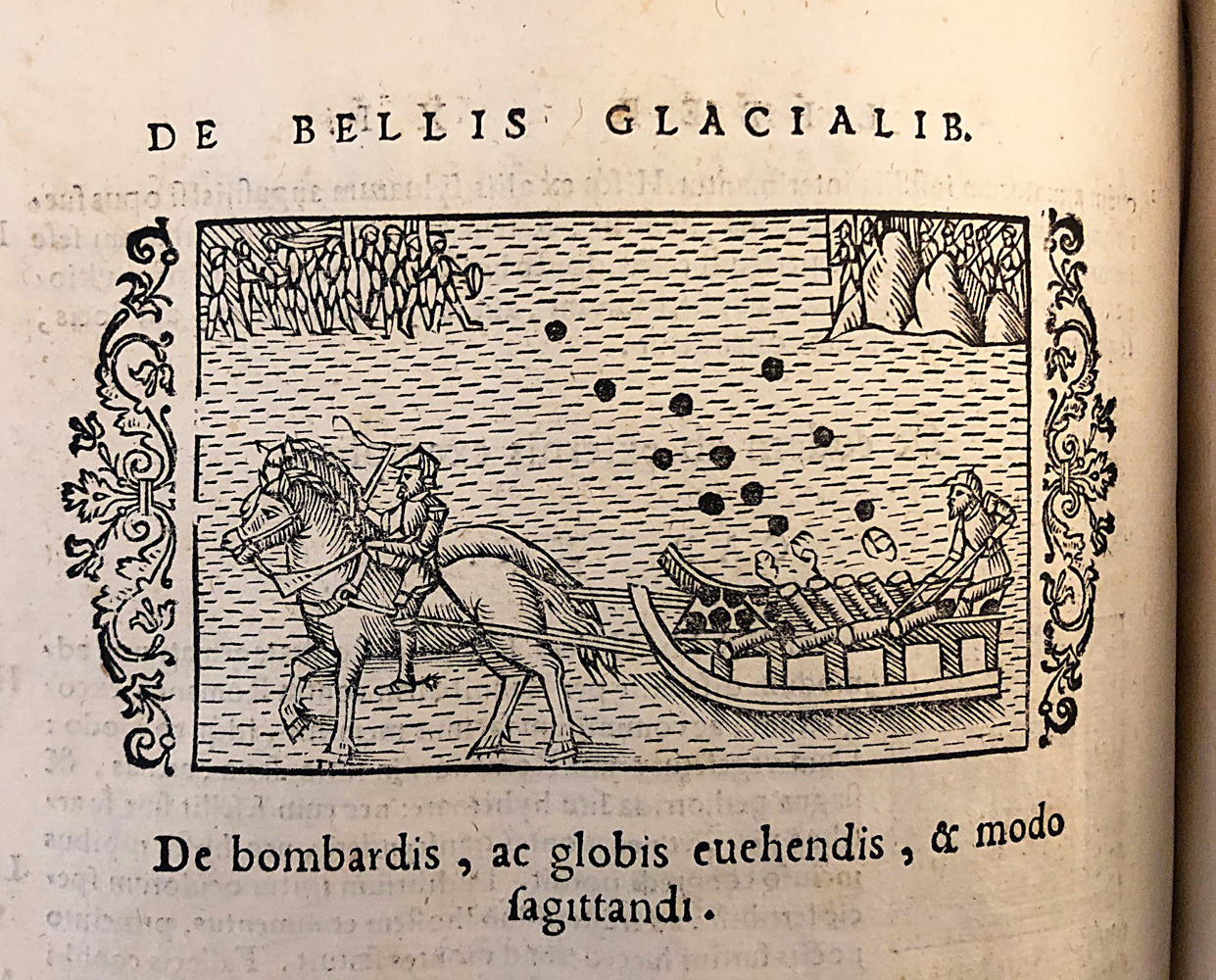

Maxwell notes that “[t]he phrase becomes immediately intelligible … if one has just been reading Olaus Magnus’s account of fighting on the ice, which fills the eleventh book of his polymath work. [Book XI of Olaus is titled “De Bellis Glacialibus.” I’m no Latin scholar, but I’m guessing that means “On Frozen Warfare.”] Here Shakespeare could have seen a series of vivid woodcut pictures that accompanied an astonishingly comprehensive description of northern strategies for war in winter, including the use of sleds for transporting and firing cannon [see accompanying illustration]…. The rapid firing off the cannonballs from the sledge … rather qualifies the offence to decorum felt by one Victorian critic: ‘What a ridiculous position it must have been to see a king, in full armour, smiting down a sledded man …..’”

Maxwell also points to the fact that the 1567 edition of Olaus specifically refers to a contemporary battle on ice involving both Danes and Poles. (Which battle? Oh, come now. Surely you remember “the climactic battle between the forces of Christian II, the Danish King, and Sten Sture the Younger, the anti-unionist regent of Sweden …, [which] took place on the ice at Lake Asunden in Västergötland on 20 January 1520”?)

Those who are interested in pursuing this subject further may wish to take a look at “Shakespeare, Olaus Magnus, and Monsters of the Deep,” by Rhodri Lewis (also the author of the fascinating work “Hamlet and the Vision of Darkness” [2017]), published in Notes and Queries, March 2018. After a hat-tip to Maxwell — noting that the crux discussed here “need perplex us no more” — Lewis suggests that Olaus also “casts one of [King Lear’s] more famous lines into much sharper relief. In particular, I want to propose that Shakespeare found in the Historia the insigne verbum — the arresting image, idea, or phrase — that would become the germ of the ‘monsters of the deep’ that trouble Albany’s moral imagination.” (See Lear, Act IV, scene 2 — “Humanity must perforce prey on itself / Like monsters of the deep.”).

For me, however, the connection to Hamlet alone was sufficient to lead me to add Olaus to my collection of Shakespearian sources. And while I agree with Lewis that Maxwell has driven the nail to the board and resolved this textual crux forever, I still feel that sled-mounted cannons would create all sorts of Third Law difficulties (Newton not Asimov; laws of motion, not robotics) that would have lent a Marx Brothers quality to the battles that Olaus has described. (Anyone who has played air hockey can appreciate this.) Olaus may have said it, and Shakespeare may have accepted it, but I for one can’t believe that it actually happened.

Or could it have? While researching this post I discovered that Russia used war sleds in the “Winter War” with Finland that broke out just after the beginning of World War II. (The Finnish-Soviet conflict was the war for winter-sports-and-war buffs, since the biathlon-trained Finnish soldiers fought on skis.) Of course, the Russian sleds were used mainly for transport and reconnaissance, and to the extent they were armed it was with light weaponry such as machine guns. The momentum of machine-gun bullets would not have diverted the heavy Russian war sleds (photographs available online) as grievously as cannonballs shot from the horse-drawn, one-man sledge depicted by Olaus.

-Prospero

2 thoughts on “Beyond the Page: Resolving a Shakespearian “Crux”; or Fighting on Sleds”