The Civil War, The War of Northern Aggression, War Between the States: no matter what you may call it, the Civil War was a brutal conflict that tore deep holes in our national fabric. Moreover, it is these same Civil War-era questions–ones of equity, economy, and injustice–that are still hot-button topics in modern political discourse. To understand this intranational conflict, we look to what was left behind, to what can still be read, preserved, digested, and understood: words.

Lincoln’s Bid

In early 1860, a Philadelphia printing press released a list of “prominent candidates” for the presidency: Lincoln was not among them. Yet, in May of 1860, he was elected as the Republican Party’s presidential candidate. It seems an impossible feat; how did the party have such a change of heart in such a short period of time?

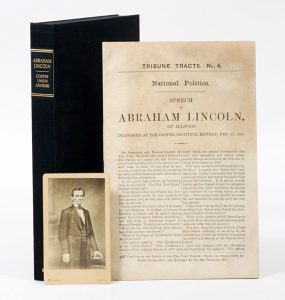

A kind of publicity package that came from Lincoln’s Cooper Institute speech. Pictured: A Tribune pamphlet-copy of Lincoln’s Cooper Institute speech, accompanied by a renowned carte-de-visite of Lincoln, captured by Civil War photographer Matthew Brady. Lincoln was believed to have said that ‘Brady and the Cooper Institute made me president.’

For many, it was his Cooper Union Address that sealed the deal. Early in the race, William Henry Seward of New York had emerged as a clear favorite. Yet, many Republicans–especially many within New York came to dislike him. He was often framed as an “extremist”; because he saw the relationship between slavery and freedom irreconcilable and preached a higher law than the Constitution, many within his party were eager to find a more moderate candidate.

And with Abraham Lincoln they did. Lincoln understood that to deliver a great speech at the Cooper Union Institute was to appear as a well-seasoned, well-read moderate anti-slavery candidate. Lincoln appealed to the the party members’ nationalistic ideals and deep patriotism–a product of the growing secessionist climate of the United States–by centering his speech on the fact that the majority of the Founding Fathers did not, in fact, support slavery. Consulting the official proceedings from Congress, Debates on the Federal Constitution, and the Congressional Globe, Lincoln was able to make a historically grounded, and nearly irrefutable case against slavery. After news of his address spread, Republicans from other states in New England invited Lincoln to come speak in their cities. Ultimately, the president-to-be spoke in eleven cities in twelve days. It was the publicity Lincoln received from these 7,000 words, first delivered on a snowy night in front of 1500 men at the Young Men’s Central Republican Union of New York, that Lincoln the vote at the Republican Convention of 1860. The stirring success of the Cooper Union Address is intimately and inextricably linked to the Lincoln presidency.

Understanding Heroes post-war

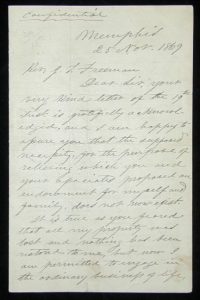

Lincoln’s words tell the story of a North embittered and enraged by a deeply bigoted and intransigent South. However, this rare and provocative letter from Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy, presents a new perspective. Davis, who expresses his gratitude for the Reverend’s support in this letter, hints too at his own post-war plight. After being captured and held in egregious conditions by Northern forces, Davis was all but forced out of the United States. While he ultimately returned to the United States, money was hard to come by; Davis published a history of the Confederacy–which did not sell–and attempted to start up an insurance company, which flopped as well. Davis never regained his citizenship during his life, as he refused to pledge allegiance to the postwar, United States flag. His citizenship was recognized posthumously in 1978; Davis was, most certainly, the chief defender, apologist, and advocate for the vanquished Confederacy.

It is in this letter that Davis’s life is so well captured; he writes of his personal hardships and struggles, while at the same time expressing his love and support of a South that was changing quickly before his eyes. This letter is definitely a historical artifact–but, it is also more than that. It is a document that turns one man, a man who has been vilified by and excluded from the dominant historical narrative, into just another human, a man whose life (like so many others’ lives) was profoundly impacted by the outcome of the Civil War.

From pre-war to post-war, these documents tell stories from all perspectives, places, and prejudices. Together, they paint a picture of a war that was not one-sided, with good guys and bad guys; instead, this document-collage shows a conflict that was deeply complicated, historically entrenched, and highly emotional. To comprehend past conflict is also to comprehend its consequences and its modern legacies. Certainly, we are still a nation divided. And, we are also a nation united: united by passion, by want, by fear. It is this story, of division and unity, that is rooted just as much in the Civil War as it is rooted in modern day. It is when we look at what was left behind that we truly understand was once was, and what is now.

by: Abigail Haber

Interested in purchasing these exceptionally rare items for yourself? Below are the links:

https://www.manhattanrarebooks.com/pages/books/383/jefferson-davis/autograph-letter-signed