(Re)discovering Darkness: The Photographs of Brassai

Ever since the advent of the camera, the intense desire to preserve, that is, to capture things and people and places as they are so that future people can see things as they were, persists across time and space. Photography is an art which is claimed by many and belongs to no one; yet, there are certain pioneers who have revolutionized photography, rendering it at times a journalistic endeavor, at times a way of bridging human understanding, and at times a vehicle through which to create artistic masterpieces. One of those pioneers was Hungarian-French photographer Brassai.

Trained as a sculptor, painter, and journalist, Brassai, born originally as Gyula Halasz identified as a fine art photographer, choosing to disassociate himself with the “pickpocket photographers” that emerged in Europe during the 1930s. During his nightly walks around Montparnasse, a district infamous for its debauchery and capitalism, Brassai deftly captured the nighttime scenes with his camera. The camera was not simply a tool for him; rather it was a instrument of creativity.

And create he did. He learned to avoid halo or overly sharp lighting in his photographs by using elements of the street scenes–walls, trees, bridge–to mask the street lights, converting direct into indirect lighting whenever possible. Photographing in hazy, rainy weather proved best, providing the atmosphere that would absorb or reflect light and attenuate excessive contrasts. Brassai would venture into the most deserted, empty streets. In order to determine shutter time, he would smoke cigarettes, which helped to gauge the kind of lighting and shadows on “set”. Brassai’s photographs were distinctly, darkly Paris; marked by indirect light, hazy shadows, and obscured faces, Brassai did not merely capture the people of the night, but also the night itself.

The photographer believed not simply in the communicatory nature of the photograph, but rather in its revealing and transformative nature, writing that “my ambition has always been to show the everyday city as if we were discovering it for the first time.” There is a kind of theatricality, certainly, in what he does: take the piercing gaze of two women at a bar, for example–lips pursed, head cocked, light reflecting and scintillating off the back mirror of the bar.

When photographing this book, I left the page with this photograph open. Throughout the day, I remember, with remarkable clarity, the way in which these two women’s eyes seemed to follow me around the room, their expressions so very blank yet at the same time so very animated. The Modern Mona Lisas, if you will?

Brassai did not merely view the photo as a static object, but rather imbued a dynamism and aliveness into each moment. Brassai did not capture things as they were, but as what they could be.

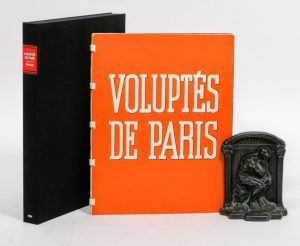

It was his 1935 collections “Voluptes de Paris” (Pleasure of Paris), which earned him international acclaim. Its scandalous subject matter caused a stir amidst the upper echelons of Parisian society, men and women who only dared to venture to Montparnasse through the photograph; I think this relationship is what makes Brassai so revolutionary. In the interwar era–marked by deep disillusionment, class tensions, and social anxieties–Brassai brought two sectors of society together in unexpected and exciting ways. He, paradoxically, exposed the people of Montparnasse through obscurity, through shadow, and through darkness.

It is Diane Arbus, a skilled photographer in her own right, who sums it up best: “Brassai taught me something about obscurity, because for years I had been hipped on clarity. Lately, it’s been striking me how I really love what I can’t see in a photograph. In Brassai […] there is the element of actual physical darkness, and it’s very thrilling to see darkness again.” Brassai has served, and will continue to serve, as a model photographer, a prime example of how one’s sharp eye and fearless artistry can shape society.

by: Abigail Haber

Stunned (as I am) by the photos? Inspired by, what many call, Brassai’s “living eye”? Here are the links to Brassai’s work, as well as the work of some other notable photographers, available for purchase on the Manhattan Rare Book Company website.

https://www.manhattanrarebooks.com/pages/books/1952/brassai/voluptes-de-paris-pleasures-of-paris

Check out the “Art and Photobooks” tab on our website for more stunning pieces!